BEREA, Ohio -- Except for the fluky 2007 season, the Browns haven't had a top 10-ranked offense since Ronald Reagan was president.

Conservatism has been the preferred offensive philosophy through recent coaching regimes. Defensive-minded head coaches have conditioned us to accept the football bromide, "You've got to run the football to win, especially in this climate." How's that worked out?

When Browns President Mike Holmgren hired his first -- and he says last -- head coach, he followed two criteria. Young and offensive-minded. The fact that new coach Pat Shurmur is a coaching descendant of Holmgren and runs the same precise, pass-first, West Coast offense that took NFL teams to six Super Bowl championships in nine appearances was the clincher, of course.

But mention the phrase "West Coast offense" in cold, blue-collar Cleveland and you meet instant skepticism. That won't work here, not when the Lake Erie winds howl in December. This is a running town.

In truth, the foundation of the West Coast offense was laid in Cleveland under Paul Brown and then built upon by Bill Walsh in Cincinnati when he became Brown's top offensive assistant with the Bengals.

"The sanskrit, if you will, was Cleveland, 1948," said Brown's son, Mike, the president of the Cincinnati Bengals.

"If you listen to the real professionals in the game, it started in Cleveland," said Ron Wolf, former Green Bay Packers general manager.

Not only that, one of the men credited -- or blamed -- for coining the tag, West Coast offense, was none other than former Browns quarterback Bernie Kosar. Not only that, the coach who devised the blueprint for slowing down the West Coast offense is former Browns coach Bill Belichick.

And Holmgren, who proved as Green Bay coach in the 1990s that the West Coast offense could prosper in cold and windy weather, is now the top Browns executive.

Adding it all up, the question should not be: Can the West Coast offense work in Cleveland? A better question is: What took them so long to bring it back?

The West Coast principles

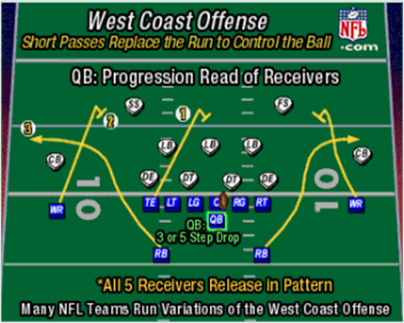

The oversimplification of the Walsh system is that it's a ball-control passing game that de-emphasizes the run. Think shorter pass routes and quicker throws, equivalent to extended handoffs.

"You want to strive for balance," said Holmgren, who learned under Walsh. "The indicator, as much as anything, was the fact there were a few more pass plays that you had in the game plan that would substitute normally where other teams might call runs. So you had a lot of passes in the 5- to 8-yard area, and you were OK with that, as opposed to handing the ball off and running."

There is built-in flexibility to adjust to your team's talent. That was the staple of Walsh's philosophy in Cincinnati and San Francisco.

Philadelphia's Andy Reid, whom Holmgren said follows Walsh's offense as closely as any coach now purporting to run it, said: "We led the league in long passing [last year]. Our deep game is pretty good. But, listen, everybody does it different. You've seen quarterbacks in that thing with howitzers -- Brett Favre, Donovan McNabb. Michael [Vick's] got a big gun. And you've seen the Joe Montanas."

As a player, Kosar favored a more downfield approach to the passing game. But he marveled at the "highly intricate" West Coast offense.

"The principles involve understanding defenses and really sound route-running," he said. "[Walsh] created holes in that 0- to 10-yard range. It really was beautiful. I mean, to run tight ends through and replace them and get a guy open five yards from the line of scrimmage with 10 yards of space, it's really beautiful to pull that off."

Brown admired Walsh's creativity in adapting his system to his players.

"Everybody now has a West Coast offense," he said. "I know what Bill did. It was distinctive. It was hugely successful and he deserves credit for it. He adapted to the talent he had. In my mind, the West Coast offense was the short passing game with option routes, catching the ball and immediately turning upfield and trying to split the defenders."

But it goes deeper than that. Walsh explained the principles in his book, "Finding the Winning Edge." Belichick considers the book a coach's Bible, the greatest piece of football literature ever authored. Belichick declined to be interviewed for this story.

Walsh wrote: "The West Coast offense is really more of a philosophy and a methodical approach to teaching than it is a set of plays or formations. While it certainly has come to mean a ball-control passing game based on timing, rhythm, and precision, it also describes an entire offensive structure from play schematics, preparation, installation, implementation, game planning, execution, and, perhaps most importantly, total attention to every detail."

Shurmur's definition of the system follows Walsh's comments closely.

"It's the way you practice," Shurmur said. "Not so much about no pads or beating guys up. It's about a quicker pace at practice, where you're up to game speed because the passing game is about timing, rhythm and execution. Thirty-two guys might give you 32 answers or different bullet points of what they think it is, but fundamentally it starts with what you tell the quarterback and execution."

The history of the West Coast

Paul Brown's Cleveland Browns offensive teams of the late 1940s and '50s were years ahead of their contemporaries. Brown's passing concepts were so advanced that his quarterback, Otto Graham, could stand free and wait for longer patterns to develop.

Brown's end product was the result of meticulous planning and preparation that created favorable matchups in his passing game. He took the same system to Cincinnati when he founded and coached the Bengals in the late 1960s. Walsh, first hired as the Bengals quarterback coach, then seized upon those principles and took the offense to another level.

"The numbering system that the old Cleveland Browns created and used and then adopted for the Bengals was the language of the West Coast offense," Mike Brown said. "What it was, was a system where you called the protections and the backfield flow by a number, and then you attached a tag to the number -- a verbal description -- to describe the patterns the receivers would run."

Early on, the Bengals emulated Paul Brown's vertical passing attack because they had a strong-armed quarterback named Greg Cook. But Cook's career was cut short by injury, forcing Walsh to adjust to journeyman thrower Virgil Carter in 1970.

"Virgil could not throw the ball far with great strength or accuracy, but he was very quick-thinking and he could throw short patterns effectively and he could move, so you could roll out and you could hit shorter patterns," Brown said. "And that was probably where Bill started with the short throws that became the hallmark of the West Coast offense.

"When Bill got to California, he first had Montana and they looked pretty much like what we would have looked like here. Although there were probably more short throws, it wasn't as significant as it became later with Steve Young. With Steve Young is when the West Coast offense really reached its climax. They could get rid of the ball so fast that you couldn't rush them effectively."

That ability to adjust to the quarterback's talents was a core of the system. It is why Holmgren's passing game was more vertical with Brett Favre in Green Bay than it was in Seattle with Matt Hasselbeck.

"You couldn't have the coach be so tied in to a system that you wouldn't let the [quarterback] flourish," Holmgren said. "Then you're making a mistake."

Naming the West Coast

There are two stories of how the West Coast offense got its name.

One is that when the NFC rival New York Giants finally conquered Walsh and the 49ers in the 1985 season NFC Championship, after two previous post-season losses, coach Bill Parcells sneered to reporters, "What do you think of that West Coast offense now?"

The name didn't stick, however, until a few years later when Kosar used it in a interview with a national football writer.

"Actually Mike [Holmgren] used to bust my chops about it," Kosar said. "It's an unfair simplification of a highly intricate offense. The knowledge it takes, the understanding of coverages, running guys through zones and replacing them with receivers and hitting them in full stride. When they're running it right, like Frisco in the late '80s, they made something very complex look like throwing against air, just pitch and catch."

Holmgren is not a fan of the offense's nickname. "That was the phrase that was coined after Bill kind of installed everything and the fact that it was a little bit different than the thump, crush, kill stuff," he said.

"I didn't resent it. I just thought that anybody that worked for Bill and then went on, or worked for me and went on, they kind of said they ran the West Coast offense. That wasn't altogether true because everybody put their own stamp on and things evolved. There were a couple of us that pretty much stuck with the 49ers plan, I guess, more than the others. Andy [Reid] stayed the closest to what we did."

Defending the West Coast

As Parcells' defensive coordinator with the Giants, Belichick had the task of creating gameplans to stop Joe Montana, Jerry Rice & Company in the mid-1980s. After losing in the playoffs in San Francisco's championship seasons of 1981 and '84, Belichick formulated a blueprint to slow down the offense.

By the time Belichick came to Cleveland as head coach, his plan was tried and true. On a Monday night early in the 1993 season, the Browns forced three interceptions and a fumble by Young and three dropped passes by Rice in a 23-13 upset win in Cleveland Stadium. Young would have his greatest year the following season, winning league MVP honors and taking the 49ers to their fifth championship.

"The key to defending that style offense is understanding the basic principles of it," said Carl Banks, who played linebacker for Belichick in New York and Cleveland. "Your defenders have to be good enough to disrupt timing. Basically, you've got to put speed bumps in the defense for the wide receivers in that offense. Most of the passing yards come after the catch.

"An effective West Coast offense doesn't give up a lot of sacks, so the mistake a lot of teams make -- you saw it against the Packers all year [in 2010] -- is teams were devising pass rush schemes before devising schemes to disrupt the timing.

"It's a waste of time to think you'll come off the edge and get a sack. It won't happen because the quarterback doesn't hold the ball long enough. If you can employ a combination of good, physical play on the outside of the defense and a good pass rush inside, then you have a shot.

"You have to have some sort of disruption at the line of scrimmage. Bill thought the best way to do that was to press and jam receivers with linebackers at the line and then have another defensive back they'd have to get through. When the quarterback's back foot hits the ground and there's nobody open, that's when the pass rush becomes effective."

Kosar said, "Bill understood what the offense was trying to do. The first guy decoying and trying to clear a zone out, knowing they're going to replace it with another guy. I can still hear Bill saying, 'If a guy runs through, they're going to replace him, so anticipate the next guy coming into that zone.'

"And he would beat them up at the line of scrimmage and then push that five-yard rule as far as you can and then beat them up at every aspect."

Restoring the West Coast in Cleveland

Can the West Coast offense work on the North Coast?

Banks pointed out, "You can't run that offense effectively without good wide receivers."

The quality of the Browns receivers is an ongoing debate. But all the experts interviewed for this story had much less doubt about quarterback Colt McCoy, who has all of eight games NFL experience.

"It's probably a good offense for Colt McCoy," Banks said. "In that [AFC North] division, you don't want him holding the ball because it'll result in a lot of picks and he'll probably get knocked out of the game. So it's probably suited for him. Second-year quarterback with young, inexperienced receivers. So they predetermine their routes and get the ball out of the quarterback's hands and live with it."

Brown, who saw McCoy throw for 243 yards and two touchdowns in a 19-17 Bengals win in Cincinnati in December, said, "I like your young quarterback. I think he's got real promise -- quick-thinking, accurate, nimble-footed, quick-throwing. I think that he's a natural for this kind of thing."

Reid said, "McCoy will be very good at this. He's smart. It's timing, anticipation."

Holmgren believes the combination of McCoy and Shurmur is the right fit.

"I think some things about the offense have proven true over the years," he said. "One, while everyone would like the guy who is phenomenally physical, a la Brett Favre, who can throw the ball through the roof and all that stuff, to be successful in the offense, it's more accuracy and timing.

"So if you have a good quarterback and you can teach him the system and he's disciplined, I know it works. So Colt is those things and now we just have to see and allow him to play."

What about the Cleveland weather in December? It's no harsher than in Green Bay. The Packers ranked in the top 10 on offense in five of Holmgren's seven seasons there.

When Wolf hired Holmgren in 1992, he said he had no hesitation about bringing the West Coast offense to frigid Green Bay. He was sold when he saw Holmgren, then the 49ers offensive coordinator, roll up big numbers in San Francisco with fill-in quarterbacks Mike Moroski and Steve Bono.

So weather is not an issue. As Mike Brown pointed out, "We did it here before they did it in California."

It just didn't have a catchy nickname.

Original article:

http://www.cleveland.com/browns/index.ssf/2011/08/the_cleveland_browns_2011_offe.html

No comments:

Post a Comment